Undergraduate research expands through the CUREs model

Ongoing efforts to enhance class-wide projects brings research opportunities to more students earlier in their college career.

Janel Shoun-Smith |

As part of an overall effort to promote and expand undergraduate research at Lipscomb, the university is promoting Course Based Undergraduate Research Experiences (CUREs). In this research model, research and creative inquiry are embedded into the course curriculum.

CUREs are intended to build on the usual one-on-one mentor-based model to allow undergraduate students on a broader scale to be introduced to and to carry out research, said Florah Mhlanga, associate provost of undergraduate academic affairs, who has advocated for research at the undergraduate level throughout her career and who helped establish Lipscomb’s Student Scholars Symposium over a decade ago to highlight undergraduate research.

“Many students are excluded from the mentor-mentee research model,” noted Mhlanga. “This is particularly true of students who are shy and do not have the confidence to actively seek out undergraduate research opportunities from faculty, students with limited knowledge of career structures and those who may not have performed well in their courses. Entry into a CURE only requires undergraduate students to enroll in the course. As such many more students can be exposed to research compared to the traditional mentor-mentee approach.”

In addition, “one of the major benefits of CUREs is that they broaden the participation of students from underrepresented groups thereby creating educational equity, said Mhlanga.

In kinesiology, students have been studying the optimal hours of quality sleep needed by student athletes.

CUREs offered this academic year included courses in biology, kinesiology, engineering, English, computing, business, music, nursing, and law, justice and society, among other disciplines.

- In kinesiology, students have been studying the optimal hours of quality sleep needed by student athletes.

- In engineering students are comparing energy usage from a mix of scientific sources and non-scientific sources.

- English students are researching a historical artifact or cultural practice used in a novel.

- Nursing students are delving into the effectiveness of certain drugs on diabetic weight loss and blood glucose management.

Jan Harris, professor of English, teaches History of the English Language, a course that covers linguistics, social history and language history. Each year she has her students conduct a semester-long research project on a topic of their choice that is related to the class, such as the evolution of dialects, the development of constructed languages (those that are created for a specific purpose, such as for fictional characters in television show), analyzing types of propaganda or the history of a culture as relate to language.

Throughout the course the students formulate research questions based on their reading, they create a research proposal, an annotated bibliography and once the paper is written they must develop it into an academic presentation to present to the class, said Harris.

“We try to simulate what they would do at an academic conference,” said Harris. “So we have a Q & A session, and I model good questions for them to ask or questions they would be most likely to hear at such a conference. I have invited past students to come present their paper and the students ask them about the topic and about how they completed the project.

“Because they get to spend some time on the front end thinking about what they are interested in, they stay more motivated about the research,” said Harris.

Many students in CUREs, such as this student Abigail Miller, present their research findings at the annual Student Scholars Symposium.

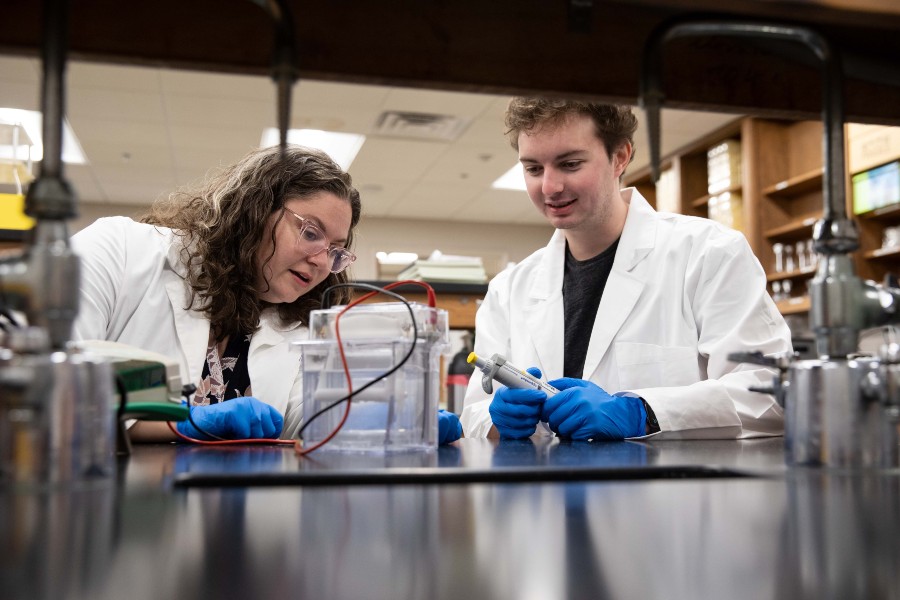

Seven years ago, Dr. Bonny Millimaki, professor of biomolecular science, revamped her Developmental Genetics course from a traditionally observation-based lab to a hands-on application lab where undergraduates learn the steps of the scientific method by doing.

“I think it is more valuable to teach our students the way in which we discover new knowledge and not just what that knowledge is,” said Millimaki, who designed an experiment where students introduce a potential teratogen (an agent which causes malformation of an embryo) to zebrafish embryos.

Students research which chemical to test—teratogens from fluoride to bitter leaf, from seizure medications to BPS, a BPA alternative. The students’ experiments do not always yield conclusive results, but “It’s not about what your data show,” said Millimaki. “It is about how well you understand the experimental design and understand what your results actually mean. It is about learning the scientific process.”

The provost’s office of undergraduate academic affairs is also actively working with several course instructors to develop CUREs and is collaborating with the associate chair of general education to embed CURES into first-year general education courses.

Embedding CURES in freshman level courses exposes students to research and creativity early on. Benefits for students who participate in CUREs from freshman to senior year include increased gains in content knowledge, improved analytical and technical skills and increased confidence in conducting research, said Mhlanga.

Seven years ago, Dr. Bonny Millimaki, professor of biomolecular science, revamped her Developmental Genetics course from a traditionally observation-based lab to a CUREs lab where undergraduates learn the steps of the scientific method by doing.

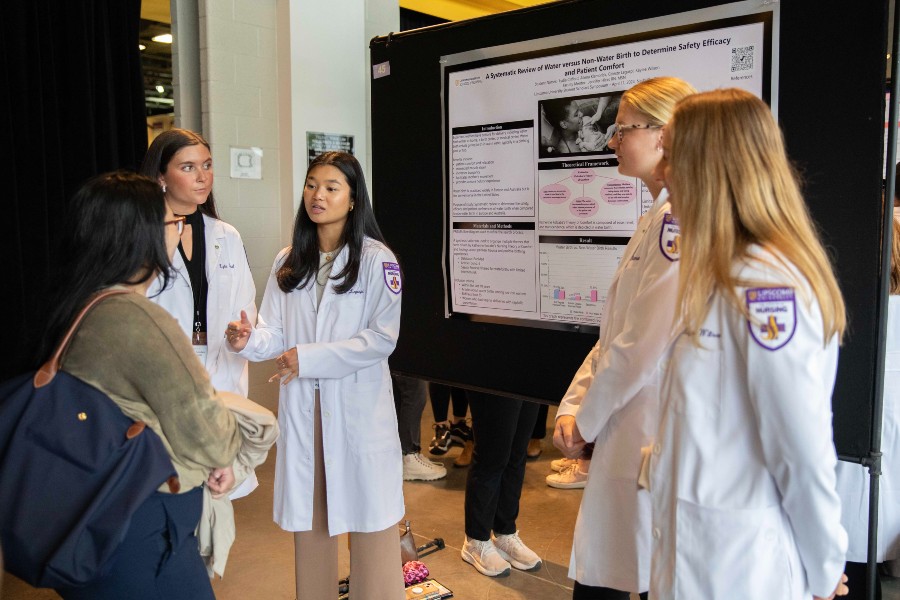

“Nurses need to have an understanding of nursing research and to know how to find and use it in their daily practice,” said Jennifer Hicks, an instructor in Lipscomb’s nursing program.

Consequently every Lipscomb nursing student is required to take a nursing research and theory course to learn how to search for current literature by nurse scientists or those in other disciplines to answer questions about nursing care issues, and to translate the new knowledge found into practice.

In 2024, Hicks’ 51 students presented nine scholarly systematic review research poster projects on topics of their interest, including how forensic nurses can promote healthy recovery for victims of trauma, virtual reality strategies to help children cope with pain of intravenous catheter insertions, comparisons of water birth versus conventional birth, and factors that contribute to nurses’ burnout, to name a few.

“I tell the students that someday they will wonder, ‘Why do we provide care the way that we do?’, and it won’t suffice to just say, ‘There has got to be a better way!' You must be able to conduct a literature search to answer your question and bring the most current evidence to your unit leadership to effectively translate current care practices into evidence-based care,” said Hicks.

“Nurses need to have an understanding of nursing research and to know how to find and use it in their daily practice,” said Jennifer Hicks, an instructor in Lipscomb’s nursing program.

Brandi Kellett, chair of the Department of English and Modern Languages and associate chair of general education, is partnering with Mhlanga to introduce students to the basics of research and inquiry in the Lipscomb Experience course, the introductory course to the general education curriculum.

“In Lipscomb Experience, students are taught to think critically about their own bias as they begin an intentional process of asking big questions,” said Kellett. “This pursuit of inquiry helps prepare them to consider sources, engage in experiential and academic research and begin a lifelong journey into thinking critically about our ideas and norms.”

English and Modern Languages was one of the first departments to pilot a CURE course: Reading and Writing Professionally, said Kellett.

“Nothing helps a student grow more than inspiring them to engage in their own research and work,” said Kellett “In English in particular, every major writes at least three-to-four long form, multi-sourced original research papers, in addition to producing three-to-four pieces of their own creative work as well.”