There’s no place like home for TN R-WIN nursing cohort

Nursing students live, learn and will practice health care in rural areas of Tennessee through Lipscomb’s grant-funded initiative.

Janel Shoun-Smith | 615-966-7078 |

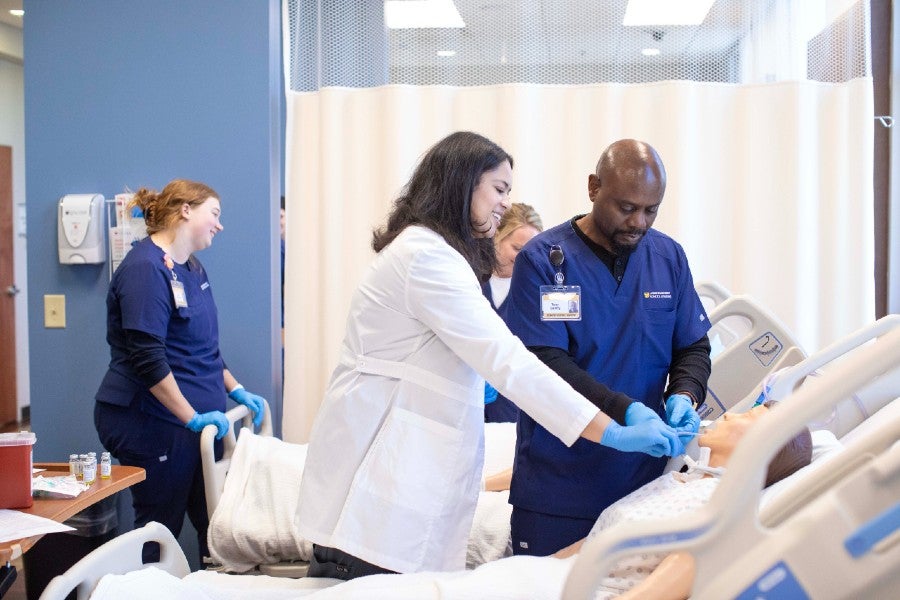

Tony Gentry, a social worker who lives in Giles County, works in Lipscomb's Health Simulation Lab, along with his fellow classmates in Lipscomb's inaugural cohort of the Tennessee Rural Workforce Initiative for Nursing.

Chelsia Harris

Chelsia Harris, a first generation college graduate and Lipscomb’s executive director of nursing, is well aware of what it is like to grow up in a rural area.

Her own upbringing in rural Arkansas and the start of her nursing career in a small community hospital in an underserved rural area gave her firsthand experience with the challenges of under-resourced rural health care and instilled a passion to bring the best care available to patients in small towns.

So when the Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development’s (TDLWD) Rural Healthcare Initiatives Program announced a new opportunity for grant money in the field of health care, Harris and the School of Nursing jumped on the opportunity and corralled the school’s community partners and faculty to establish a program to train nurses who also hold a passion for rural health care.

Lipscomb’s Tennessee Rural Workforce Initiative for Nursing (TN R-WIN) is designed to address the critical nursing shortage in Tennessee’s rural communities by recruiting students from underserved areas to complete Lipscomb’s Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing (ABSN) program.

TDLWD is providing comprehensive financial support for the first two semesters of the four-semester ABSN program, including full tuition, fees, supplies, travel expenses and overnight accommodations when necessary.

Ashley Jackson

The ABSN program is led by Assistant Program Director Ashley Jackson (MBA ’22), who also grew up in Tennessee’s Robertson County, where the six-person TN R-WIN cohort began their clinical training this past fall.

Jackson, who lived in White House, suffers from Celiac Disease and Type 1 Diabetes, so she became well familiar with the long drive to Nashville to see medical specialists as she grew up.

“I have two hearts when it comes to health care, one for providing access to those who don’t have everything they need readily accessible, and secondly I’m a huge believer in preventative care,” said Jackson. “I believe that knowledge is power, and that you can’t do better until you know better. That is the challenge for nurses, to bridge that gap of knowledge.”

That’s what the TN R-WIN students will be able to provide after finishing the hybrid online and in-person program. Hailing from Montgomery, Sumner, Giles and Williamson counties and trained at TriStar NorthCrest Medical Center in Robertson County, the first cohort will not only have health care experience within a rural health care setting, but they also all have personal ties to such areas.

“We looked for students who are passionate about rural health care,” said Harris.

Kimberly Linderman, a member of the current cohort, lives in Spring Hill and has experience setting up allergy clinics in rural areas.

Kimberly Linderman, a member of the current cohort, grew up in Nolensville (before Nashville’s urban growth overtook the small town) and today lives in Spring Hill (where she moved before it also became much more urban). The 36-year-old has experience as a pharmacy tech, an allergy tech and then as a clinical liaison who traveled to rural areas for years to set up allergy clinics for United Allergy Services.

As she set up the clinics, she saw the burden many patients faced having to drive hours multiple times a week to get allergy shots. She would love to someday become a nurse practitioner and set up a clinic in a rural area, her favorite place to live, she said.

Health care in rural areas “feels more family-oriented and smaller, so you can get closer to your patients,” said Linderman. “I love learning about them and making them feel loved and heard. You can tell they don’t always get that kind of care, because it seems to mean a lot to them.”

Tony Gentry, a social worker at Nashville’s Centennial Medical Center who lives in Giles County, certainly understands the travel obstacles that small town patients face.

Raised in Pulaski, Gentry already has experience working with the Department of Child Services in rural areas of Tennessee and working as a caregiver for his mother and grandmother. He’s looking forward to being able to work with people in a different way as a nurse.

“I enjoy working with people, meeting people and engaging with folks to build effective, long-lasting relationships,” said Gentry, who hopes to become a cardiac nurse. “I enjoy providing care and comfort to patients during their vulnerable time.”

Due to the lack of accessible specialty health care, many cardiac patients in rural areas can only be stabilized locally and then must be sent to an urban hospital for cardiac procedures such as a heart stint, said Gentry.

As a cardiac nurse, Gentry says he can be part of the solution by recognizing symptoms of potential heart problems and helping the health care team determine the best course of treatment.

The TN R-WIN students having personal ties to a rural area is important for building a sustainable health care staff, said Harris, who noted that more often than not, urban-raised health care providers do not readily thrive in the under-resourced remote areas.

Similarly, faculty also have ties to rural Robertson County, Jackson who works from Lipscomb’s campus in Nashville and Hannah Bagwell, who lives in Robertson and oversees the cohort’s clinical studies at NorthCrest.

“The special thing about rural health care is that you truly get to know each other,” said Jackson. “It is hard to care for someone’s physical needs without attending to their spiritual needs, and rural health care emphasizes that even more. You get to know the resources you have really well. You become almost a resource manager. You need to be able to provide discharge teaching, such as when the patient needs to follow up, where they can do that and how it will happen.”

Discussions are ongoing to replicate the TN R-WIN model with other Tennessee counties, said Harris.

Ashley Jackson, assistant program director, grew up in Robertson County and is passionate about brining more knowledge and health care providers to Tennessee's rural areas.

The ABSN was developed to allow students who already hold a bachelor’s degree or higher to quickly transition (in 16 months) into a nursing career, but that population is also less likely to qualify for financial aid, so Harris, who taught for several years at the College of the Ozarks where 90% of the students came from homes below the poverty line, is always looking for new sources of financial assistance.

Although he has to drive hours to get to his in-person clinical sites, Gentry says the online format of the ABSN program “is great! It makes it much easier for people like me. It gives me the ability to work and continue my education, and to be able to do all that successfully.”

“What excites me about the ABSN program, is that we are helping students be equipped for their God-given calling,” said Jackson, noting that the ABSN had 120 applicants for 20 spots in fall 2025. “If you are called to nursing, we don’t want you to have any disadvantages just because this is a second career. The students talk about how refreshing it is to see a program structured in this way.”

“It is a great set-up to study at home but still get lots of good experience at the clinicals,” said Linderman. “The teachers are so supportive and encouraging. They want us to succeed and I can really feel that.”