Juan Rojas teaches not just students, but robots as well

Engineering assistant professor teams with undergraduates to teach robots how to learn faster.

By Janel Shoun Smith |

Many people may think it’s hard enough to teach students how to complete a task.

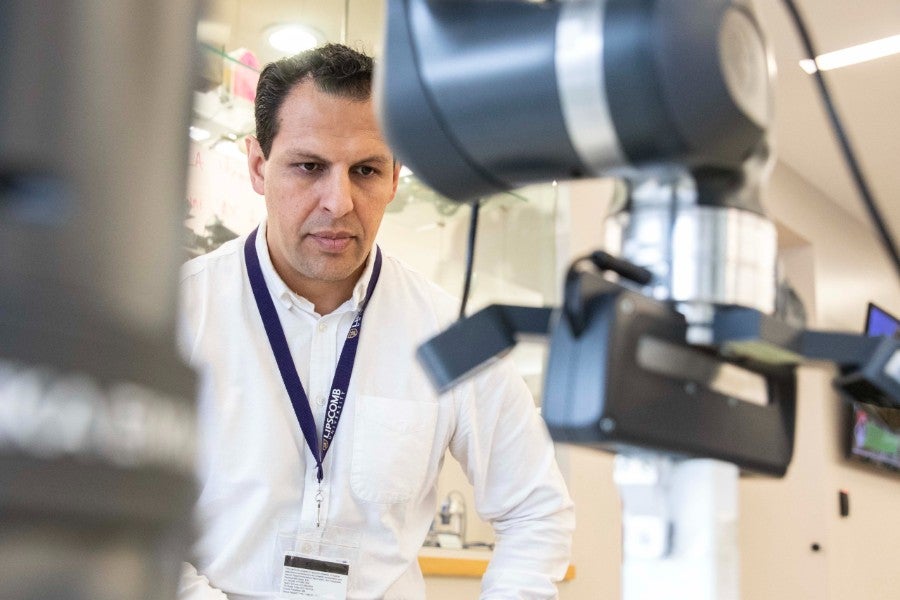

Dr. Juan Rojas, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, however, goes a couple of steps beyond that. He spends his days teaching robots how to complete a task, and then teaching students how to teach robots to complete a task.

Sounds like an endless loop, but that concept is actually apt for how Rojas is working to make robots learn faster.

He is using concepts of symmetry in computer coding, allowing the robot to replicate its past experience with a task many times over and in many different ways, without actually physically doing it. The robot learns the best way to complete a task by practicing it in its head first, then when the actual movement of the robot occurs, it is based on all its experiences that it didn’t actually have to run in real-world time.

Basically, Rojas is working to make robots learn faster, an outcome that could save a great deal of time, money and human labor programming robots on the front end.

“Over the last decade or so, robotics engineers have used deep reinforcement learning, a kind of AI that rewards the robot when it does the right thing. The traditional setup of this reward system though takes a long time for the robot to learn,” said Rojas.

“In the industrial world, that can cause safety and logistics problems, becoming impractical. So a lot of our effort is getting the robot to learn very fast from scratch.”

Juan Rojas and members of the 2024 RoboCup team with Lipscomb’s state-of-the-art Franka Research Robot.

Rojas has been at work on this goal since his studies at Vanderbilt University in the 2000s. He went on to pursue his work at universities ranked among the top 10 in China and Hong Kong and a leading national lab in Japan. He worked as a 100 Young Talents Associate Research Professor at Guangdong University of Technology in China and was recently named as an AI Fellow at VALIENT (Vanderbilt Lab for Immersive AI Translation) at his alma mater Vanderbilt.

He also serves as an associate editor for the conference proceedings for three of the top robotics research conferences held around the world, allowing him to be continually immersed in the latest work in the field, he said.

Having published more than 60 peer-reviewed journals, conferences, and workshops and having presented at the top robotics conferences in the world, Rojas has overcome many challenges in his career, but in spring 2023, he began a new challenge: teaching undergraduates.

He envisions an intelligent robotics concentration offered through the Raymond B. Jones College of Engineering with strong undergraduate research in AI and robotics and a future robotics lab.

He’s off to a good start.

Since coming to Lipscomb, Rojas has developed a track for undergraduate students by developing introductory classes for robotics and artificial intelligence as well as an advanced robotics course that centers around research.

Students learn through the current research literature and by implementing their ideas through coding Lipscomb’s state-of-the-art Franka Research Robot, obtained in 2024 through a grant from the Louis R. Draughon Foundation.

Rojas also works with a few students each summer to continue development of the state-of-the-art system. He expects to be submitting new results for publication soon. In 2023, his summer students Brennan Cottrell (BS ’23) and Justice Roberts (BS ’24) presented a paper at a workshop that was part of the International Conference on Robots and Systems (IROS), held in Detroit, Michigan and ranked as one of the two most impactful robotics research conferences around the world.

In July 2024, a team of Rojas’ students brought in a third place finish at the international 2024 RoboCup Autonomous Robot Manipulation (ARM) Challenge Finals in Eindhoven, Netherlands, competing against top teams from around the world. It was Lipscomb’s first appearance at the event, which attracts more than 2,500 participants from more than 40 countries.

Seniors Cleiver Ruiz-Martinez, Gracelyn Grant and Kris Pesnell, sophomore Gabriel Everett, and now-alumni Courtney Stevens (BS ’24) and Joseph Laporte (BS ’24) developed algorithms to control robot manipulators in complex environments.

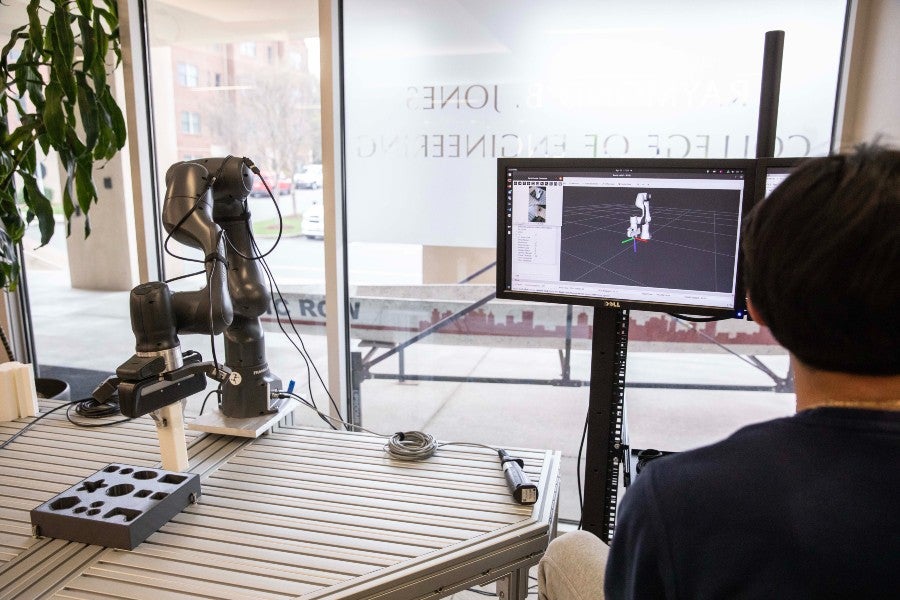

Rojas and students use high-level programming, testing and debugging to teach the robot image recognition and motion planning to carry out the task within an unknown workspace.

The 2024 event required robots to complete a recycling task: identify where each object was located, what type of object it was and which bin it should be placed in. The robot’s job was to make those decisions, pick up the objects and place them in the correct bin on its own, without a human operator. The team spent months using high-level programming, testing and debugging, to teach the robot image recognition and motion planning to carry out the task within an unknown workspace.

The three students enrolled in the spring Advanced Robotics course, are certainly enthusiastic about the AI and robotics fields. Ruiz-Martinez, a junior electrical and computer engineering major from Nashville, was part of the 2024 RoboCup team. He had participated on robotics teams in high school, but hadn’t considered it as a career until Rojas introduced him to the Franka Research Robot.

“Having something you can physically touch and see, and to see your work actually carried out, there is something really special about that,” he said, noting he hopes other students will be inspired by seeing the robot at work.

He and Faris Jugovic, a senior electrical and computer engineering major from Nashville, said they not only enjoy learning “the nitty gritty of machine learning,” but they are also excited to be part of a community of engineers working toward ambitious goals.

The students are using an open source program called SERL (Sample-Efficient Robotic Reinforcement Learning) developed through the University of California at Berkeley as a jumping off point for their own programming and are able to ask questions, watch videos of working robots and get ideas from digital online communities of AI scholars willing and excited to share.

“We can literally ask a Berkely Ph.D. a question,” said Jugovic, noting that the skills he is learning in the class “can be used in basically every field.”

“The research is important, but the community is important to advance the work,” said Ruiz-Martinez.

Franka Research Robot

For Rojas, Lipscomb’s robotics program is merely the continuation of a long road. Having earned his bachelors, master’s and doctorate in electrical and computer engineering at Vanderbilt, Rojas’ dissertation work involved teaching multiple robots to independently work with each other, reacting to each other’s actions.

In the next stage of his career he worked on what he calls “robot introspection,” teaching robots to be able to identify and analyze their own failure so that they can then work toward recovery. Then he began to focus on his current question, how can we make robots learn these things faster.

Most recently he won a $15,000 grant from the Open Scholarship Catalytic Awards Program for his project titled "Minutes-to-Mastery: Accelerating Generalizable Robotic Manipulation with Efficient Group-Theoretic Deep Reinforcement Learning,” and presented “World Models for General Surgical Grasping” at the Robotics Science and Systems conference in Delft Netherlands in July 2024.

Having already secured about $40,000 in equipment for Lipscomb’s robotics programs, Rojas keeps his ambitions high. He has set his sights on obtaining a grant offered by the National Science Foundation intended to encourage undergraduate robotics programs.

“No matter what stage of experience the students are in, I enjoy seeing the students’ initiative and seeing them surprise me with what they can achieve,” said Rojas.

“Research of this type is very complicated and having undergraduates become contributing authors is a really big challenge,” said Rojas, who has previously worked with up to 12 graduate students at a time, “but research is like a bicycle: at the beginning it is very hard to get moving, but once it gets some momentum, it gets easier.”

Faris Jugovic, a senior electrical and computer engineering major from Nashville, manually operates the Franks Research Robot.