Delving into the classics to create contemporary

Lipscomb artists’ creativity and academic scholarship fuel Nashville’s identity as a theatrically artistic city.

Janel Shoun-Smith | 615-966-7078 |

Hamlet and Nashville Shakespeare Theatre's co-production of Hamlet. Photo by Sarah Johnson.

Nashville may have earned its “Music City” moniker due to the rise of Country music, but there’s no doubt that the South’s “It City” also has a thriving arts scene, from classical music to contemporary art, from opera to children’s theater.

Nat McIntyre

When Nashville’s premier cultural organizations begin to hatch a new idea for their next production, it is more often than not that an expert from Lipscomb’s George Shinn College of Entertainment & the Arts will be called upon.

Lipscomb’s arts faculty bring to these local community organizations a wealth of professional experience, uncommon professionalism, creativity and an approach to any concept informed by years of research and scholarship.

This past spring brought an unusually unique collaboration as Lipscomb partnered with the Nashville Shakespeare Festival to stage Shakespeare’s Hamlet, bringing thousands of Nashville students to campus to see the Bard’s most famous play.

Nat McIntyre, assistant professor of theatre, directed a version of the play that combined modern music and a mashup of modern and classical styles for costumes and sets to bring to life a creative vision all his own. McIntyre has been on the Lipscomb faculty for six years, but in that time he has had an impact on the city’s culture far beyond Lipscomb’s on-campus stages.

He most recently acted in Nashville Repertory Theatre’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time and in Rabbit Room Theatre’s The Hiding Place. Prior to that, he directed A Streetcar Named Desire for Nashville Repertory and Henry V and Macbeth for Nashville Shakespeare Festival.

Every decision made to produce a work of art is based on an understanding of the work’s cultural context in history, so cutting your artistic teeth on Shakespeare is particularly valuable for future artists, said McIntyre, who earned his MFA from The Old Globe Theatre at the University of San Diego, California.

“I think when you learn classical, it is the basis for everything else in theater,” he said. “You learn how to take any theatrical work and make it relevant to any audience. It teaches you how to find the theme that rings true today and to find productions that speak to a common audience.”

At the beginning of any production, McIntyre begins by researching the work, especially the language, he said. “I start with the words, especially the words that are repeated a lot. Repeated words make you think about themes,” he said. “I read the original version as Shakespeare first wrote it. That can often help with the correct pronunciation, the rhythm of the piece and themes.

“You think about the time the work was written and research what was going on at that time in the world. I also investigated past productions of Hamlet and pinpointed what resonated about those versions,” he said.

Nat McIntyre (right) in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time at Nashville Repertory Theatre. Photo by Chad Driver.

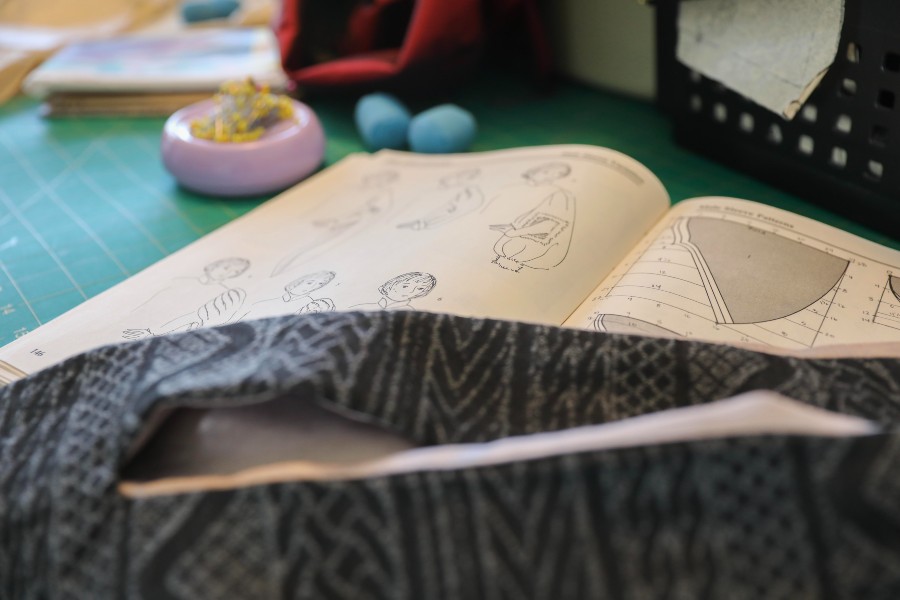

June Kingsbury, Lipscomb’s costume designer and costume shop manager, was given a challenge for Hamlet to mix two time periods: 15th century Danish medieval and modern. She tackled it by hitting the history books to research patterns of medieval period garments and combined those shapes with modern fabrics to look something akin to Project Runway’s weirder looks, she said.

June Kingsbury

“I am creating my own fashion line for this production – something that looks a little more like runway fashion,” she said. “It gave me permission to go bizarre and a little wild but still use the shapes of the medieval period.”

Kingsbury has no lack of experience creating wholly new looks for a unique creative vision. She has been costuming Nashville theater productions since 2000, including a production of Cinderella for Nashville Opera that had a “beach blanket bingo” theme and a production of Rigoletto with a film noire black and white theme. Over the past 10 years for the Nashville Shakespeare Festival, she has designed “birdlike” fashion for Love’s Labour’s Lost, pan-Asian costumes for Macbeth and World War II themed costumes for Much Ado About Nothing.

Everything from the time period to the venue, must be considered. Costumes for an outdoor amphitheater may need to be different from costumes for an intimate black box theater or garments for a work that is being filmed with cameras up close, said Kingsbury.

June Kingsbury was given a challenge for Hamlet to mix two time periods: 15th century Danish medieval and modern.

Using particular color schemes or repeated style elements can reinforce the themes for the audience or help them keep track of who is who on stage or understand when time has passed, especially important in a Shakespearean work that school-age students are attending, she said.

She’s collected many art and fashion history books over the years to help with inspiration and authenticity. She also watches period dramas for ideas. “You have to think about how fashion relates to the politics and society of the time.

Having a broad understanding of history and culture is very important,” she said.

Kingsbury says her longevity with Nashville’s theatrical scene is not only due to her creativity but also to her reliability. One needs to be organized and prepared and must plan ahead,” she said. “Organization leaves room for letting things bloom. You have to have all the elements ready and give them some time to simmer.”

Kingsbury tackled Hamlet's costumes by hitting the history books to research patterns of medieval period garments and combined those shapes with modern fabrics.

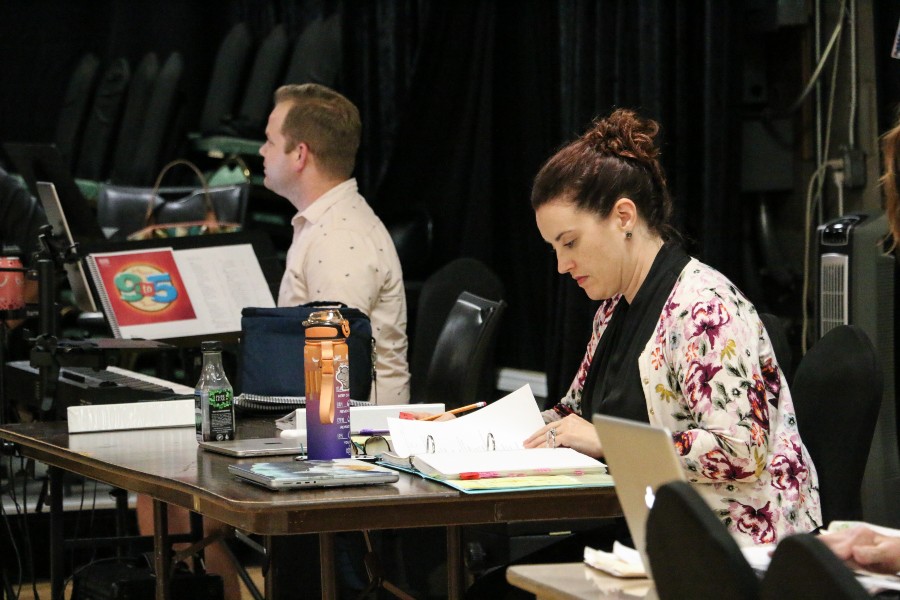

Adding to her eight-year history of directing various works for Nashville Repertory and Studio Tenn Theatre Company, Beki Baker, associate professor and chair of Lipscomb’s theatre department directed 9 to 5 for Nashville Repertory in fall 2023 and Driving Miss Daisy for Studio Tenn this past spring.

“The research that I do influences my teaching, directing and my work one-on-one with students,” said Baker. Working in Nashville’s professional theater scene allows her to remain up to date in her field and bring that knowledge back to students, she said.

“The main research is the time period. You must understand different aspects of the show: the playwright’s intent, the use of music, the story and the physical layout,” said Baker.

For her work on 9 to 5, a musical based on the cult classic film and addressing the massive cultural shifts for working women in the 1970s, Baker researched the status of women in the workforce in the 1970s, learning that women made up 50% of the workforce at that time but were paid 60% less than men. Even today, women are paid only 80 cents for every dollar earned by men and four in 10 women report gender discrimination in the workforce.

Beki Baker

“I wanted the show to encourage women and those marginalized to work together and link arms, and not work against each other,” said Baker. “If we work together, we can make real change happen. I hope the audience saw that the people who came before them overcame some real challenges, and now they have an opportunity to continue that forward and be part of that story.”

For Driving Miss Daisy, a play that tackles racism and antisemitism in the 1940s through the ’70s, Baker assigned a student, Justice Orrand, as her director’s assistant. Orrand put together a 20-page dramaturgical packet on related themes and events in the time period such as Jewish culture in Atlanta, the civil rights movement and Jim Crow laws.

“I’m a very thorough, organized and efficient director. I really plan ahead and that makes the experience better for the company and the actors,” said Baker. “That way when I come into the process, I can be highly collaborative. I believe the product is better by all working together. Lipscomb’s artists care about the interpersonal experience. We are not means-to-an-end kind of people.”

For her work on 9 to 5, a musical based on the cult classic film and addressing the massive cultural shifts for working women in the 1970s, Baker researched the status of women in the workforce in the 1970s.

Christopher Bailey, a visiting professor in the School of Music, has worked as musical director for Nashville Children’s Theatre off and on for six years. His most thoroughly researched production with the troupe came this past spring, he said. The Gingerbread Kid was fully developed by the theatre and world premiered on its stage in January.

Christopher Bailey

As it was a completely brand new show, the team was able to workshop the production in the summer of 2023, a rarity in today’s theater industry.

“It was a three-day process, where we learned the show and did a read- and sing-through for an invited audience on the third day. Then we were able to go back to the writers’ room and discuss what worked and what didn’t and how we can make it better,” said Bailey.

The team continued to re-work aspects of the show, about the magical child of a baking couple, throughout the fall of 2023, and one of the show’s songs, “Life Is Sweet,” was selected to perform at the Theatre for Young Audiences-USA national conference.

A music director gets the final say of the score and voicings and serves as a go-between for the director and the cast, said Bailey. Depending on the soundscape of the show, the musical director could be directing an orchestra or a smaller band or could serve as a track engineer, mixing recorded tracks with live performers.

The Gingerbread Kid is a pop music show, but there are not many pop musicals in children’s theater, said Bailey, so he looked to recordings of pop music with strong background vocal arrangements, and he borrowed the style seen in Sara Bareilles’ Waitress, a Broadway show that used her pop music vocal style.

Bailey looked to recordings of pop music with strong background vocal arrangements for The Gingerbread Kid, and he borrowed the style seen in Sara Bareilles’ Waitress. Photo by Michael Scott Evans.

“I am a singer first, so what I really love is shaping the style of the show in terms of the vocal landscape,” said Bailey. “Sometimes we get a score that is written for 36 people, and we have 9 or 16 in the cast. It is my job to reduce that to something that honors the score but is singable and sounds good. Sometimes the composer may write melodies that turn out to be unsingable when paired with lyrics. You don’t know those things until you get into the process.”

He also brought his long-time experience in children’s theater to bear, knowing the sound capabilities of the theater space, the size of the cast and the number of costume changes all make a difference in how the singing sounds during the show. He also watches recordings of musicals to see how the cast and director handle demanding, fast-paced scores like Hamilton.

“It’s really important to me to stay current in creative downloading. You must go see shows; you must listen to things; you must look at things at the top of the industry,” he said. “Ultimately, all of us in the arts want to make good work. We can do that at any level, you just have to have forethought on how to make it happen.”