The ancient meets the cutting edge

Ph.D. candidates’ project for the Lanier Center partners with engineering to create 3-D replicas of ancient pottery.

By janel Shoun-Smith | 615-966-7078 |

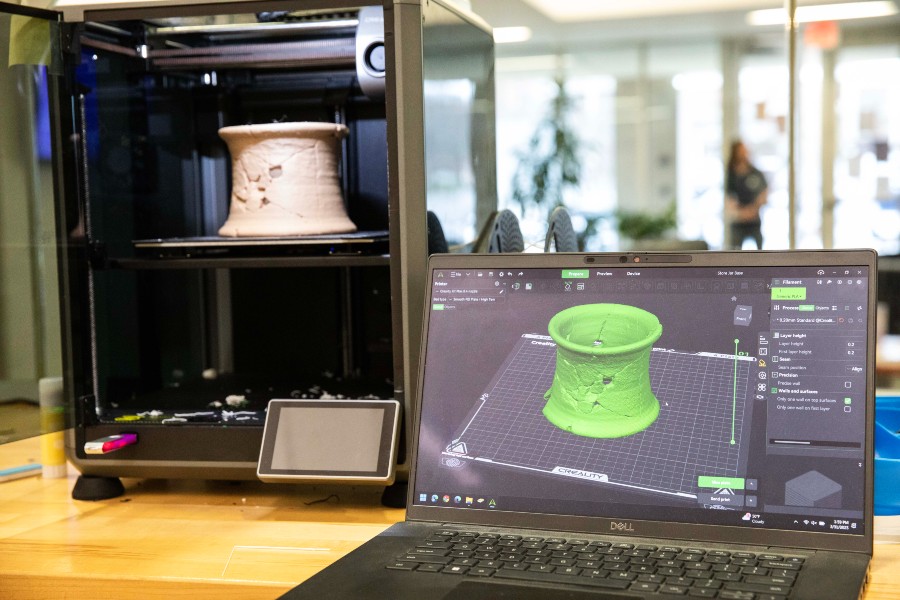

Sam Wright (right), of the engineering college, and Terry Nichols (left), of the Lanier Center for Archaeology, watch one of the Raymond B. Jones College of Engineering's 3-D printers at work creating a replica of pottery for the Lanier Center for Archaeology.

Doctoral student Terry Nichols has always lived at the intersection of the head and the heart.

As a minister enrolled in seminary, he also worked in information technology. Then after discovering archeology, he continued to work in IT even while he studied archeology and worked on digs in Virginia, the Karnak Temple in Egypt, and Tel Gezer, Tel Burna and Khirbet ’Ether in Israel.

Now this school year, he has merged the two to begin an extra-curricular project in digital archaeology for the Lanier Center for Archaeology to create 3-D printed copies of pottery discovered in the Israel Tel Gezer Excavation Site.

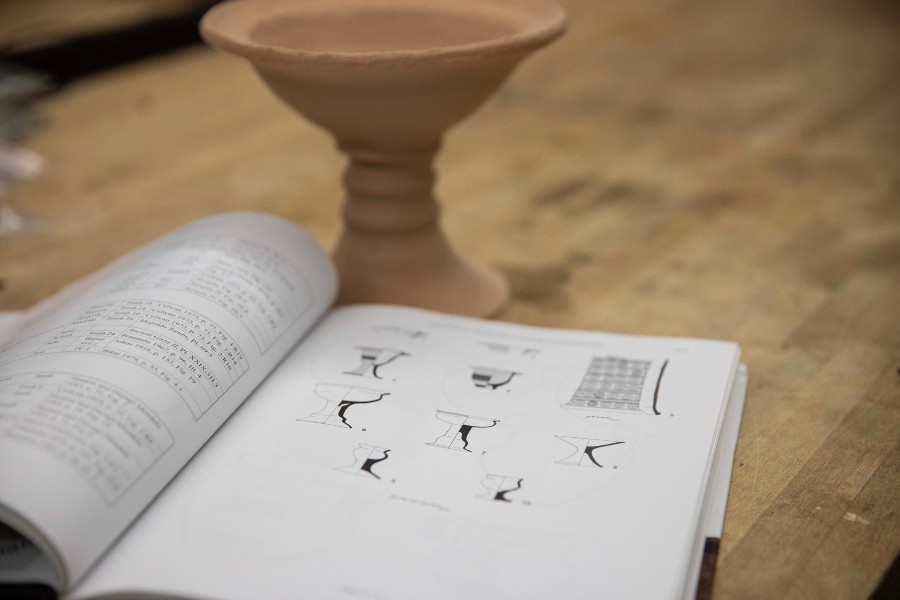

The 3-D printed chalice and jar holder that have been manufactured so far through the engineering college's 3-D printers.

Nichols, now a user services specialist in Lipscomb’s IT department, is also working on his Ph.D. in archaeology of the ancient Near East at Lanier and has teamed up with Sam Wright, assistant professor in the Raymond B. Jones College of Engineering, to create the copies of artifacts, eventually allowing Lipscomb’s students to see and hold in-person copies of artifacts that are most often required to remain in the nation where they were discovered.

The pair are still in the “proof of concept phase,” said Nichols, and have created two pieces so far—a chalice and a jar base—but the hope is reproduce up to 25 artifacts to allow students, who normally have to use photos and descriptions to learn how to identify the artifacts, to be able to see, touch and hold a replication that looks almost exactly like the original.

The team started with pottery. “Where we dig, there were no coins in that time period, so we have to learn to read the pottery to understand what we are excavating,” said Nichols. “The more familiar you are with the forms and shapes of pottery, the better you can recognize how to fit all the pieces together. There’s no end to pottery!”

Sam Wright (left), of the engineering college, and Terry Nichols (right), of the Lanier Center for Archaeology, have partnered to produce 3-D printed replicas of pottery to enhance students' learning in the Lanier Center for Archaeology.

Nichols and Steve Ortiz, director of the Lanier Center, selected for printing the 25 Tel Gezer artifacts from the hundreds available that would be the best for educational use on campus. The goal is to print the five most important pieces in the 2024-2025 school year.

The prototype piece was a 16-centimeter, Iron Age II chalice, from the King Solomon era. The second piece was a 17-centimeter tall jar base, used in the ancient world to hold jars without flat bottoms upright. Other targeted pieces include a storage jar with an LMLK seal from the time of King Hezekiah in Judah, two examples of a uniquely decorated bowl known today as the “Gezer bowl,” and a model of the nearly six-meter inscription, Ramesses II's Hittite Peace Treaty, from the Karnak Temple.

The Lanier Center sent teams to the Tel Gezer Excavation site for 10 seasons and is now in the process of analyzing and publishing research based on the finds there, but artifacts discovered at Tel Gezer, an ancient city located in the foothills of the Judaean Mountains, must be kept in Israel by law. Lipscomb students must either travel to Israel during summers to analyze the pieces in person or use images and records on campus for their studies and research.

The 3-D image of the original chalice, created from photos Nichols took in the lab and fed into computer software to create a 3-D image that users can move around on the screen.

During digs, students most often find sherds (fragments of ceramics) and use a book of illustrations showing a profile image of various styles of pottery from different time periods over a century to make a “field call,” identifying the time period of the artifact, said Nichols. When multiple found sherds make up one piece of pottery, the teams can rebuild the piece using the sherds back in the lab in Israel.

But with 3-D printing, “we can take it one step further and create the whole pot” for students in Nashville, said Nichols.

During his last trip to Israel in summer 2024, Nichols took photos and scans of each targeted piece from every angle using a 3-D camera and 3-D scanner. He photographed each piece inside and out and every crevice from every angle.

A 3-D printer manufactures a replica of an artifact along with the 3-D computer image the printer worked from to create this jar holder. in Lanier's artifact collection.

All the images were fed into a software computer program that combines them all to make a 3-D image that can be manipulated on the computer. That image is converted into an STL file, making it a matrix that can be read by a 3-D printer.

Lipscomb has seven 3-D printers in its David Scobey Innovation Lab, said Wright, who is training a student to be able to print out the replicas of ancient artifacts. With a detailed enough image and the proper coding, the printer can replicate even the texture on the original pottery. The pieces can later be painted to look just like the original.

Printing takes from eight hours to several days, depending on the size of the piece, said Wright. The proper resolution and printer speed must be coded into the 3-D printer to match the scope and intricacy of the project, he said. Even moisture can affect the outcome.

The 3-D image of the original jar holder, created from photos Nichols took in the lab and fed into computer software to create a 3-D image that users can move around on the screen.

So these projects will be good problem-solving exercises for engineering students, especially for those who want to go into additive manufacturing, said Wright.

Nichols, originally from New York, holds two master’s in theology and divinity from Liberty University and was a working pastor, IT professional and in pre-Ph.D. studies at seminary when he discovered archaeology. It was at Tel Gezer where he discovered his love for the field, having volunteered to go on a dig there.

There he met Lipscomb’s Ortiz. “I did one dig, for fun really, and it changed my life,” said Nichols.

After that first excavation, he moved to Texas in 2016 to study at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary which hosted the Lanier Center before it moved to Lipscomb in 2020. He moved to Nashville to continue his Ph.D. studies at Lipscomb and joined the IT staff at the university.

During digs, students use this book of illustrations to identify the style and era of pottery fragments, but these 3-D replicas can give students a clearer picture of the pottery from different eras before they go on the digs.

His primary interest is in the Late Bronze Age in Canaan and its connections to Egypt, with his dissertation focusing on the aftermath in Canaan of the invasion by Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah. He will be traveling with a Lipscomb team to excavate at the Karnak temple in Egypt and hopes to finish his dissertation this year. His sub-specialty, however, is digital archeology, which is often used in Egyptian archaeology, Nichols said.

As far as academic disciplines go, incorporating 3-D printing into archaeology is fairly new, he said.

“I think this is where the field is headed. Digital archaeology is a very broad field including everything from databases to digital visual images,” said Nichols. “It’s been around for 30 years, but it hasn’t been a cohesive field. For example, databases were mostly localized and not linked across the field until the last 15 years or so.”

Nichols has dreams of producing the replications for sale at academic conferences or to other archaeology programs that could use them. The Tel Gezer site has produced some particularly rare artifacts that are museum-quality, he said. Those pieces could be replicated to provide in-person, daily use of the important finds for archaeology students on campuses, he said.